Berlin to Burladingen, and Back

June 12, 2014

The weather was unseasonably warm on the Alb. While Berlin’s skies were overcast and gray, raindrops dripping from every balcony and eave, Stuttgart’s sun was shining. A filmy blue sky unrolled over deeply green hills as we drove away from the city and into the rural landscape of the Schwäbische Alb. It’s called the Swabian Jura in English, but that feels so wrong to say, I just won’t.

I forget how pretty the Alb is when I’m not there, especially in late spring and early summer, when the trees have bloomed and the fields sprout full of wild daisies, dandelions and purple wildflowers. I love the unreal color of green coating the grass, the way the landscape looks freshly dipped in dew.

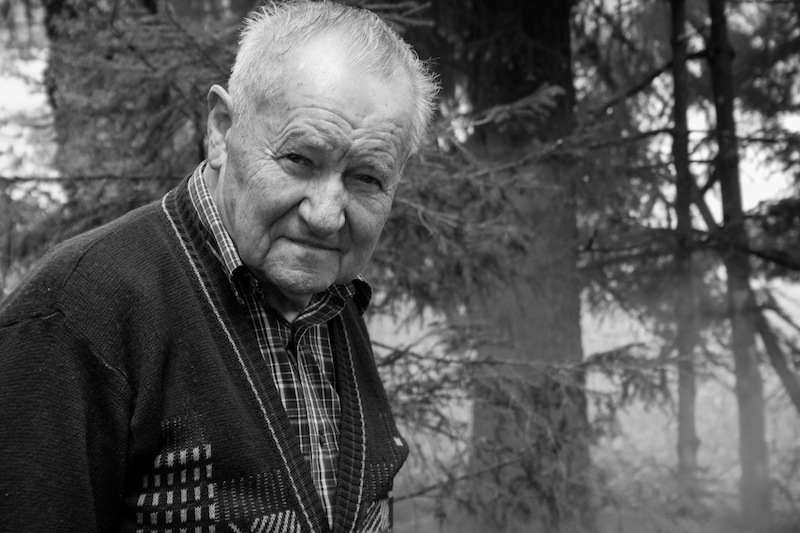

My brother and I are on our way to our grandfather’s house. My uncle is driving, we’re chatting about the upcoming world cup and which nations are the happiest on Earth. He outlines our program for the weekend. When you only fly south for a long weekend, your hours are tightly regulated. My aunt and uncle are coming for dinner, the next day, if the weather holds, we’ll go grilling on the Eichland. There’s talk of Eurovision.

Burladingen is all talk, it’s always all talk. By which I mean, we start a constant stream of visiting and chatting and catching up from the moment we set foot in my grandfather’s house to the moment we leave. And in the Southern Germany I know, there’s no talking without something tasty to go with it – creamy mushrooms wrapped up in crepes, Danishes and coffee, homemade pizza finished with a round of my grandfather’s bootleg raspberry liqueur, dark bread for breakfast with butter and jam, cake and cake and cake. “It’s not my fault if you go home hungry,” my grandfather says. It certainly is not.

On Saturday morning, after a drawn-out brunch with my aunt and cousins, we determine that the weather is good enough to go up to the Eichland, my grandfather’s plot of land in the woods where we’d spend days on end in the summers we were down south.

We set to work when we get there. Now that we’re grown, we don’t go to the Eichland quite as often as we used to, and the grass has gone wild and the leaves and sticks are thickly strewn around the fire pit. My brother and grandfather trim twigs and chop logs for the fire. This is no charcoal and lighter fluid fire, but a breath of flame started with kindling and a match is kept alive by a careful stack of logs.

My cousin runs the motored mower across the lawn, while my aunt rakes leaves and twigs and I run the old fashioned blade mower over tenacious saplings taking root.

In no time at all, the Eichland is looking like I remember it. The fire is blazing, sending drifts of smoke into the field beyond the wire fence where dandelions burst with yellow all the way to the tree line.

We wrap potatoes in foil and set the marinated cuts of pork, halloumi, peppers and bacon over the fire and soon the smell is irresistible. We’re all going to reek of campfire, the sweetest scent of all.

A light, cool wind picks up as we sit down to eat. There’s bratwurst to be dipped in spicy mustard and wedged inside a halved slice of bread, cheese with charred edges to crust into the grass, and sparkling water with apple juice to drink from little plastic cups.

The next day, as we sit around a Sunday table laden with lunch, I can’t help but think back to the Eichland, the feeling of fat from fire-cooked steaks running down my fingers mingling with the wet, woodsy smell.

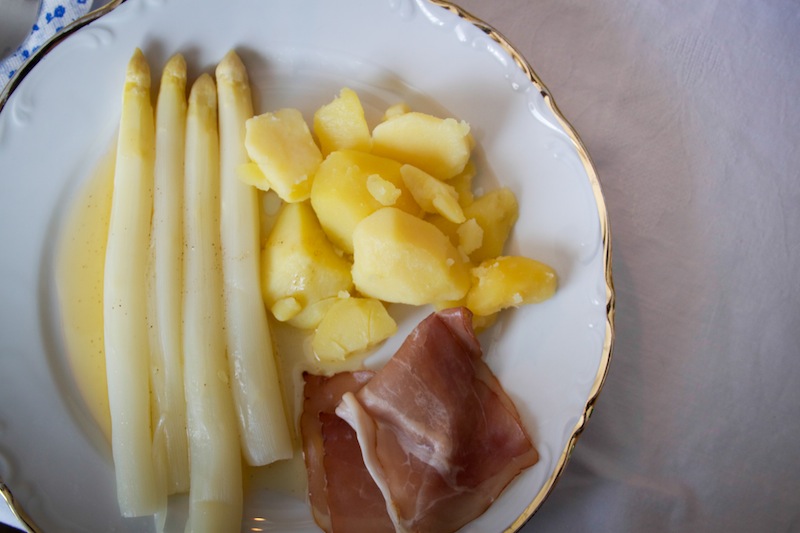

Though this is part of my Burladingen, too. A clean, white tablecloth covered with the good china, the white set with ruffled edges and thin gold line. And my family, sitting around the table. My uncle has promised me asparagus cooked the traditional German way, in buttery salt water and served with browned butter, hollandaise, ham, and dense potatoes.

My uncle says that when he cooks asparagus, he most likely melts more butter into the water than it needs, and I believe him, but think, as I dip each fragile stalk into hot browned butter that I wouldn’t do it any differently.

Of course there’s coffee, and there are cakes, too. My aunt brings a cake with currants, those bright, tart red berries that hang in bunches like shrunken, jeweled grapes. We make another pot of coffee, and long after the cakes are gone, we’re still sitting at the table, talking.